Meet Chris Carter 2.0

In September 5, Houston designated hitter Chris Carter came to the plate against Oakland starter Jeff Samardzija in the top of the sixth inning. The A’s led 3-2, and, with two outs already recorded, speedy Astros second baseman Jose Altuve danced off first base.

Samardzija’s first pitch was a 95 mph fastball right down the middle, which Carter swung straight through. If you looked at his career numbers before this season, you would’ve expected exactly that: Carter entered 2014 with 336 whiffs in 838 major league at-bats, a preposterous 40 percent strikeout rate that was the highest in baseball for anyone with as many plate appearances. By a mile.

But this was a new Carter. After starting the season slow, he’d heated up in a big way since the midway mark, going on a Bondsian power tear from July 4 to the moment he stood in the batter’s box against Samardzija: In 195 at-bats over those 50 starts, Carter had belted 22 home runs. In addition to hitting baseballs a country mile, Carter had also started to curb his bad habits by laying off breaking pitches out of the zone and taking shorter, more efficient swings at fastballs in the zone.

So after Carter swung through that first Samardzija heater, he started working the count: He fouled off a 96 mph fastball in on the hands; he let an 89 mph slider go by, low and away for ball one; he stayed right on a 96 mph fastball and fouled it back to stay alive; he let another 96 mph heater sail high for ball two; he laid off another 89 mph slider low and away to work the count full. Then came a 97 mph fastball, the kind of blazer tailing toward the outside corner the old Carter would have missed; the new Carter got just enough to foul it off.

Five minutes into the at-bat, Carter and Samardzija remained locked in a 3-2 stalemate. Oakland’s lanky righty looked in for the sign, and catcher Derek Norris called for another fastball, on the outside edge. This time, Carter was ready. The pitch zoomed in at 97 mph, and rather than take a gigantic hack, Carter took a nice, easy swing, so relaxed that his top hand quickly came off the bat.

The ball went screaming through the Oakland night, soaring well beyond the wall just left of dead center, and landing way up in the seats to give the Astros a 4-3 lead. A few minutes later, the virtual tape measure rendered its verdict: The ball had traveled 439 feet, Carter’s longest home run of the year in an at-bat that likely would have produced a strikeout one season prior:

o, what’s changed? Other than hitting more home runs than anyone else in baseball since early July, the most evident shift in Carter’s statistical profile is how he’s fared against fastballs.

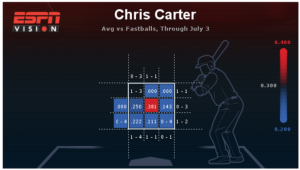

Through July 3

Fastballs Faced Whiff Rate AVG/SLG

571 30.5% .195/.438

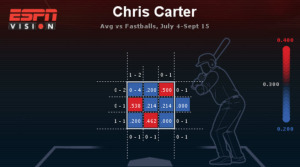

July 4 through September 15

Fastballs Faced Whiff Rate AVG/SLG

526 26.1% .284/.741

The two heat maps below help illustrate Carter’s transformation:

In the season’s first three months, Carter was essentially helpless against all fastballs unless they were thrown right down Broadway. He’s experienced some interesting changes since:

Curiously, Carter hit just .214 against middle-middle fastballs from July 4 through Monday’s action. The good news, though, is that he’s found more hot zones on pitches up and in, low and down the middle, and, yes, in that belt-high, outside-edge location that Samardzija tried to exploit only to see Carter hit the ball to Mars.

So, that’s the what. The really interesting question, though, is how? How did Carter go from being a powerful hitter who couldn’t make enough contact to being a slightly less dangerous version of 2013 Chris Davis, another batter who managed to shed the “flawed” part of the “flawed slugger” label with a breakout campaign?

Carter, who’s now 27 years old and currently batting .237/.315/.512 with 36 homers, was drafted by the Chicago White Sox in the 15th round in 2005. He was an excellent all-around hitter over his eight minor league seasons with Chicago and Oakland affiliates,2 pairing light-tower power with other broad skills. In 3,467 total plate appearances in the minors, Carter hit .283/.378/.535 while blasting 182 homers and even swiping 37 bases. Entering the 2010 season, Baseball Prospectus rated him as the 11th-best prospect in the game, while Baseball America tabbed him as the 28th. His performance and scoutable talent made him look like a future star.

ven the best prospects can sometimes struggle to adapt to the big leagues, however, and Carter was no exception. His first two cups of coffee with the A’s3 in 2010 and 2011 saw him amass just 124 plate appearances, during which he netted a .167 batting average and 41 strikeouts. The platoon-happy A’s figured Carter might prove most useful in split duty, and sure enough, they were right. In 2012, Carter smashed 16 homers and 12 doubles in 67 games, batting just .239, but with a solid .350 on-base percentage and a bulky .514 slugging average.

While those improved numbers still weren’t enough to convince the A’s that Carter would be a viable everyday hitter, the Astros were more confident. On February 4, 2013, Oakland sent Carter, pitching prospect Brad Peacock, and catching prospect Max Stassi to Houston for shortstop Jed Lowrie and relief pitcher Fernando Rodriguez. In 148 games last season, Carter mashed 29 home runs, the kind of raw power numbers a 6-foot-4, 250-pound slugger with uncommon strength would seem destined to deliver. Yet he remained a deeply flawed hitter, batting .223, posting a .320 on-base percentage that was a little light for a DH playing in a hitter’s park, and managing a modest .451 slugging mark. Even more alarmingly, he struck out 212 times, worst in the majors and the third-highest total in baseball history.

As he scuffled to start this season, Carter looked like the same guy: a dead-pull hitter who was easily seduced by Minute Maid Park’s shallow left-field Crawford Boxes, and who swung from his heels on his way to merely decent results. Behind the scenes, however, Carter was working to change his approach, and in turn his results.

This spring training, hitting coach John Mallee stressed two goals to Carter: (1) shorten the swing, and (2) change the overall approach. Unsurprisingly, it turned out those two goals were heavily connected.

“Before, the lower half of his body wasn’t leading his hands,” Mallee said this September. “When that happens, it’s tough to get a direct path to the ball, so your swing gets longer, and less accurate. So, he just kept working on leading with the lower half so that the sequence of his swing would be better, and his swing path would be better.”

Though Carter’s new habits didn’t immediately translate in the box score, Mallee saw early signs of progress from his pupil. Where Carter used to miss or foul off hittable pitches early in the count, he was now looking for them and, better still, putting them into play:

Carter augmented his physical work on swing mechanics by diligently watching more video and reading more scouting reports, which allowed him to better understand the opposing pitchers’ repertoire. That off-field work, regular playing time, and hitting the peak age at which many power hitters start to figure things out combined to make Carter more comfortable at the plate, Mallee said.

Once he was better able to identify pitches, Carter started resisting sliders and curves off the plate. And once he managed that, he was better able to focus on hitting fastballs in the zone.

“Playing part-time, you get a couple days’ rest, then you go out there, you’re a little cold, it can be tough to find that timing,” Carter said recently, agreeing with Mallee’s diagnosis. “But spending every day in the cage, then playing every day, I started getting rid of some bad habits. Before, I used to lunge at pitches too soon. Now, I do a better job of staying in the box, so I’m always in a strong position to hit.”

Carter’s next mission was mastering a skill golf instructors teach every day: swinging easy. With so many of today’s pitchers throwing 95 mph or harder, a hitter as strong as Carter can take a short, easy swing and let the pitcher’s velocity do most of the work as the ball flies off the bat.

“Guys who are big and strong, they can be tempted into swinging harder, which creates a longer swing, which can lead to lots of swings and misses,” Mallee said. “Chris recognized that all he had to do was keep that swing plane where it should be, and, just by making contact, he could hit the ball a long way.”

The final step was fully embracing the idea of driving the ball to the opposite field. Taking shorter swings allowed Carter to wait an extra split second before moving the bat, which in turn allowed him to improve his pitch recognition.

And that’s when a funny thing started happening: Carter began hitting home runs one-handed.

“He used to have a dominant top hand, so he swung two-handed, hard,” Mallee said. “The result was he would roll over on a lot of balls. Last year he added a top-hand release, so he could better stay on a proper swing path. He’s so strong, with so much bat force and leverage, that even with the top hand open, he can create so much force at impact. … Even if he gets fooled, he can still stay in the zone longer, and hit the ball hard — even one-handed.”

Against the Angels on September 3, Carter went deep twice, and his second blast was a doozy: a one-handed, opposite-field shot off the end of the bat.

He’d managed the same feat on August 25 against poor Samardzija, taking advantage of the home park’s very reachable right-center-field bleachers.

Who knows how long this current power binge will last, or if the new Carter is here to stay; Davis, after all, went from posting MVP-caliber numbers in 2013 to hitting below .200 this year before his regular-season-ending suspension. Still, absent a crystal ball, it’s safe to say Houston’s quiet slugger has found the ingredients needed to take the next step forward. Those of us not wearing Oakland green can sit back and enjoy it, for as long as it lasts.